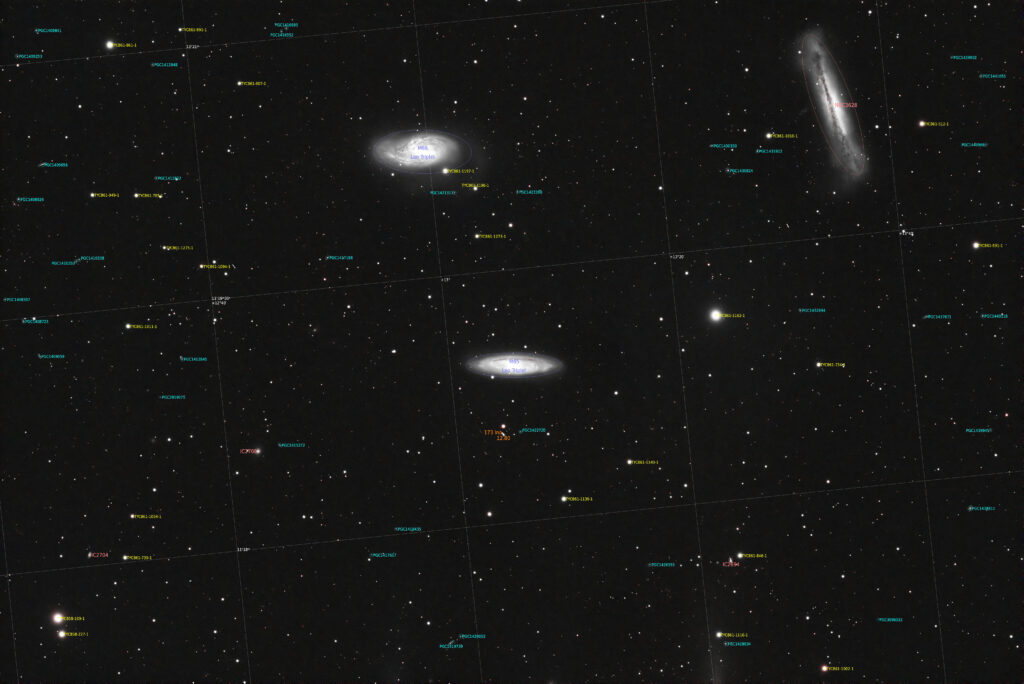

Last night, while reviewing some images I captured earlier this year of the Leo Triplet, I made an unexpected discovery. Tucked away among the spiral galaxies was a small, moving dot—asteroid 173 Ino. Twenty 120-second exposures with my William Optics FLT132 and ZWO ASI2600MC had inadvertently captured this main belt asteroid as it drifted through the frame.

It’s moments like these that remind me why I love deep-sky imaging from the observatory here on the Stoer Peninsula. You set out to photograph one thing, and the universe surprises you with another.

What is the Leo Triplet?

The Leo Triplet is a small group of interacting spiral galaxies located in the constellation Leo. The three galaxies—M65, M66, and NGC 3628—sit roughly 35 million light-years from Earth and form one of the most popular targets for astrophotographers during spring months.

What makes this grouping particularly interesting is that these galaxies are gravitationally bound and influencing each other. NGC 3628, also known as the Hamburger Galaxy due to its edge-on orientation and prominent dust lane, shows clear signs of tidal distortion from its interaction with M66. There’s even a faint tidal tail extending from NGC 3628 that stretches over 300,000 light-years—though that requires exceptionally dark skies and long integration times to capture.

From my location in the northwest Highlands, we benefit from some of the darkest skies in Europe, making targets like the Leo Triplet accessible even during nights that aren’t perfectly transparent.

Meet Asteroid 173 Ino

Now, about my accidental photobomber. If you zoom in its just below dead centre and annotated with orange text.

173 Ino is a main belt asteroid discovered on August 1, 1877, by French astronomer Alphonse Louis Nicolas Borrelly from Marseilles Observatory. Borrelly was a prolific comet and asteroid hunter, discovering 19 asteroids and several comets during his career.

The Basics

- Size: Approximately 154 kilometres in diameter

- Distance from Earth: Varies depending on orbital position, but it orbits within the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, roughly 2.2 to 3.0 AU from the Sun

- Orbital period: 4.13 years

- Classification: S-type asteroid (stony composition)

- Named after: Ino, a mortal queen in Greek mythology who became the goddess Leucothea

Why It Matters

While 173 Ino isn’t a Near-Earth Object and poses no threat to our planet, asteroids like it are crucial for understanding the early solar system. Main belt asteroids are essentially leftover building blocks from planetary formation—primitive material that never coalesced into a planet due to Jupiter’s gravitational influence.

S-type asteroids like Ino are composed primarily of silicate minerals and nickel-iron, similar to stony meteorites found on Earth. By studying their orbits, compositions, and characteristics, astronomers can piece together the conditions that existed 4.6 billion years ago when our solar system was forming.

The Technical Details

This image consisted of 20 × 120-second exposures (40 minutes total integration time) captured with my William Optics FLT132 refractor and ZWO ASI2600MC camera. The FLT132’s 132mm aperture and 925mm focal length (f/7) make it an excellent instrument for wide-field deep-sky work, while the ASI2600MC’s 26-megapixel sensor captures exceptional detail.

I processed the data in PixInsight for calibration, stacking, and initial stretching, then moved to Lightroom for final adjustments. When I had the image annotated through one of the online plate-solving services, that’s when 173 Ino revealed itself—a tiny streak that betrayed the asteroid’s motion across the two-degree field of view.

Sharing the Night Sky

Discoveries like this—even small, accidental ones—are what keep me coming back to the eyepiece and camera night after night. If you’re interested in learning more about observing from the Highlands or want to experience these dark skies yourself, I offer bespoke astronomy events here at the observatory.

I’m also running sessions through the Assynt Astronomy Club, where we explore objects like the Leo Triplet and discuss the science behind what we’re seeing. There’s something special about observing from these latitudes, under skies that still feel wild and unchanged.

Watch this space…

Leave a Reply