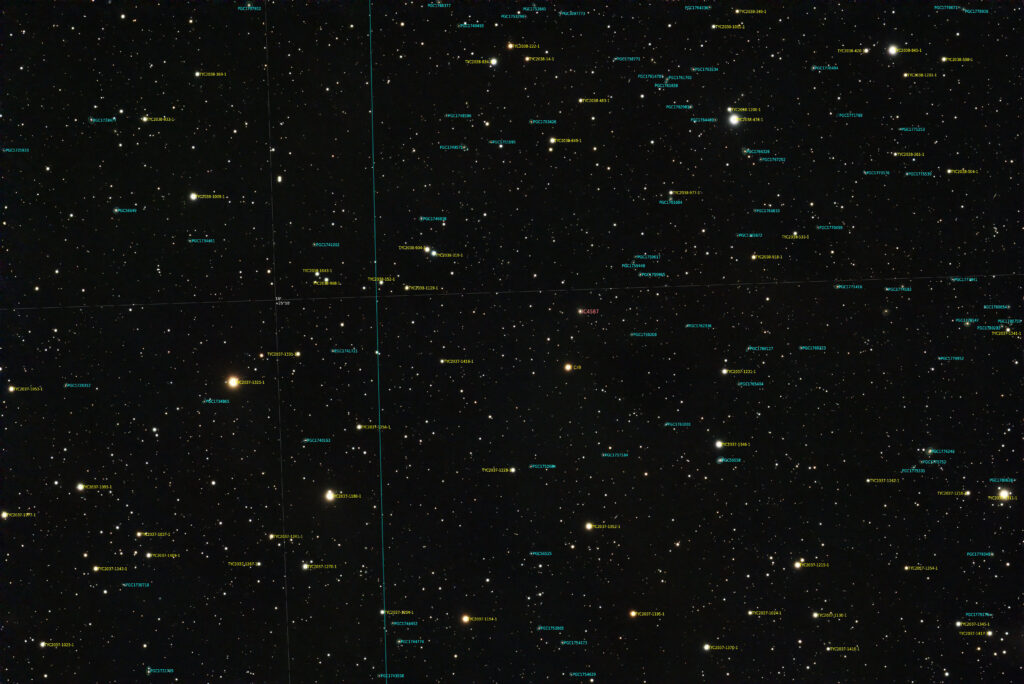

Here in the northwest Highlands, we’ve been keeping a close watch on something extraordinary: T Corona Borealis, a star system that’s been keeping astronomers on their toes for over a year now. With several thousand images captured through our William Optics FLT132 and ZWO ASI2600MC camera, we’ve been documenting what should have been one of the sky’s most dramatic events—a nova that’s now officially overdue.

What is T Corona Borealis?

T Corona Borealis (T CrB for short, or the “Blaze Star”) isn’t your typical star. It’s a binary system roughly 3,000 light-years from Earth in the constellation Corona Borealis. The system consists of a white dwarf—a dead stellar core about the size of Earth but with the mass of our Sun—locked in orbit with a red giant star. Material from the red giant steadily accumulates on the white dwarf’s surface until conditions reach a critical point. Then: ignition. The accumulated hydrogen undergoes thermonuclear fusion in a violent outburst, temporarily increasing the system’s brightness by up to 1,500 times. It’s also very rare, there are only 10 other identified recurring nova in the Milky Way which contains some 400 billion stars!

This isn’t a supernova—the star survives. T CrB does this roughly every 80 years, which is why we call it a recurring nova.

A History of Outbursts

The first recorded observation of T CrB erupting dates back to 1866, when Irish astronomer John Birmingham spotted it on May 12th. Before that, the star was too faint for naked-eye observation. It erupted again in 1946, and based on the estimated period, we expected another outburst between 2024 and 2025. Here we are in 2025, and… nothing yet.

This delay is actually scientifically interesting. Pre-eruption behaviour in recurrent novae isn’t perfectly understood, and the fact that T CrB is running late gives us valuable data about the physics at play.

It is my personal scientific opinion that each recurrence would be slightly later. If the donating red supergiant’s outer core is being stripped away to fuel fusion on the white dwarf, each time there is less to strip away and consequently slightly further away. So it stands to reason that this occurrence may not be as overdue as we would otherwise believe. Also the current prediction was based on the 1945 dip in brightness followed a year later by the nova itself. The estimated cycle was set at 80 years, 1946-1966. There was a similar dip in brightness in 2023, hence the 2024/25 prediction.

Why We’re Watching from Stoer

From our observatory on the Stoer Peninsula, we have exceptional conditions for monitoring variable stars. The dark skies here mean we can track subtle changes in brightness that might get lost in light pollution elsewhere. Over the past year, we’ve been imaging T CrB regularly, with a setup that gives us the resolution and sensitivity needed to capture precise photometric data.

Processing these images through PixInsight and Lightroom, we’ve built up a detailed light curve showing the star’s baseline behaviour. When (not if) it finally erupts, we’ll have comprehensive before-and-after data from a single consistent setup.

The Numbers

- Distance: Approximately 3,000 light-years from Earth

- Size: The white dwarf is roughly Earth-sized; the red giant companion is considerably larger at around 75 times the Sun’s radius

- Orbital period: The two stars orbit each other every 227.6 days

- Peak brightness: During eruption, T CrB reaches magnitude +2, easily visible to the naked eye

- Normal brightness: Around magnitude +10, requiring binoculars or a telescope

- Discovery: John Birmingham, 1866

- Known eruptions: 1866, 1946, and (we’re waiting) ~2025

Scientific Significance

Recurrent novae like T CrB are important laboratories for understanding stellar evolution, binary star dynamics, and thermonuclear processes. They also contribute to the chemical enrichment of galaxies—each eruption scatters processed material into space.

More practically, they help us calibrate distance measurements. The predictable relationship between a nova’s peak brightness and its subsequent decline rate (the “maximum magnitude-rate of decline” relationship) makes them useful as standard candles for measuring cosmic distances.

T CrB is particularly valuable because it’s relatively close, well-studied, and erupts on human timescales. Most astronomical events require patience across centuries or millennia. With T CrB, we get to watch stellar physics unfold within our lifetimes.

Join the Watch

If you’re interested in observing T CrB yourself—or learning more about variable star astronomy—our Assynt Astronomy Club meets regularly to share observations and techniques. We also offer bespoke events at the observatory where you can see objects like T CrB through our equipment and understand what makes them scientifically fascinating.

The star is located in Corona Borealis, visible in the evening sky during spring and summer from the northern hemisphere. When it does erupt—and it will—you’ll have about a week to catch it at peak brightness before it fades again.

What Happens Next?

We’ll keep monitoring. Every clear night, weather permitting, we’re collecting data. T CrB’s tardiness doesn’t concern us—stellar physics operates on its own schedule. The eruption could happen tonight, next month, or next year. That’s part of what makes astronomy compelling: nature doesn’t follow our timetables.

When it finally goes, we’ll be ready with our cameras, and we’ll share the data here. Until then, our image archive grows, and our understanding of this system’s baseline behaviour deepens.

Watch this space…

Leave a Reply